#2 and #3 Tallest Giant Sequoias Found - and Lost?

This feature on how Michael Taylor and Steve Sillett’s team discovered the second and third tallest giant sequoias in Sequoia National Park last summer – only for the KNP Complex Fire to rip through the area just months later – is hauntingly appropriate as the Washburn Fire burns around Yosemite National Park’s Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias.

Giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) is native to California’s Sierra Nevada and only grow in 73 disjunct groves covering less than 60 square miles. Giant sequoia is the world’s largest tree species by volume and individuals are known to live up to 3,200 years thanks to their extremely thick, fire resistant bark and rot-resistant wood.

Despite these adaptations, when 85 percent of the total acreage of giant sequoia groves burned

between 2015 and 2021, thousands of mature, majestic giant sequoias were killed. An estimated 20 percent of giant sequoias died during the 2020 and 2021 fire seasons alone, according to Save the Redwoods League (League). Check out the League’s wonderfully informative and interactive page about giant sequoia to learn more about its ecology and threats to its existence.

Drought, disease and especially wildfire have made the loss of California’s rare and beloved giant sequoias headline news, but the plight of the Southern Sierra’s sugar pine has gone largely unnoticed even as the species perishes at an alarming rate with little hope for natural regeneration alongside the more well-known sequoias.

As the hallmark species of concern, it is important to recognize that the giant sequoia situation simply illustrates the larger reality that the condition of California’s forests is precariously, abysmally bad, as Taylor, Sillett, and many others are seeing.

The ground was already crunchy, and the air was dry in early June 2021 when an elite team of big tree hunters convened to check out some exceptionally tall giant sequoias tucked away in an unassuming corner of Sequoia National Park.

The group consisted of Michael Taylor, Steve Sillett, and some of their closest friends and colleagues: Sillett’s wife and forest research partner Marie Antoine; Zane Moore, a PhD candidate in Plant Biology at the University of California, Davis who met Taylor as a teenager and has chased big trees ever since; John Montague of the League and a leading discoverer of exceedingly large diameter redwoods; Ken Fisher, the self-made billionaire founder of Fisher Investments who, as a forestry enthusiast, has befriended and assisted Taylor and Sillett in the field and behind the scenes for many years; and Fisher’s lifelong pal Ross Williams.

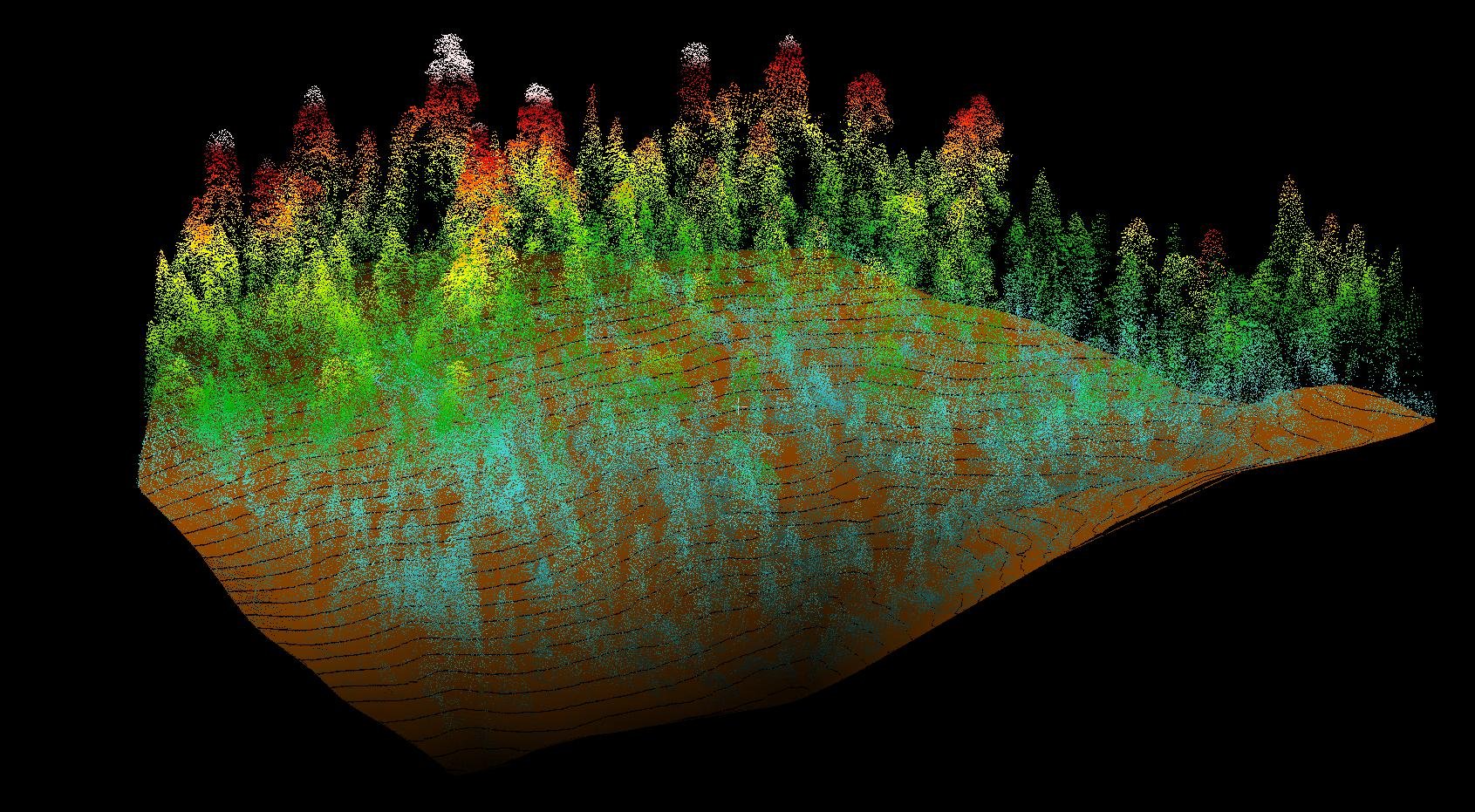

The reason for the gathering was partly social but overarchingly purposeful because everyone was excited by the prospect of finally measuring some unbelievably tall LiDAR tree “hits” that Moore and Taylor had identified about three years prior.

LiDAR, which stands for “light detection and ranging,” is a method of using lasers to create 3D maps of anything in the world – including forests full of trees.

In an interesting twist, it was young Moore who first learned how to use LiDAR data collected by land management agencies to virtually scan for tall trees. He immediately shared everything he knew with Taylor. Knowing his friend’s obsession with finding the tallest trees in the world and his ability to master and harness all things technological to this end, Moore foresaw that Taylor would grasp the power of LiDAR and run with it.

As Moore puts it, “Michael has become far more skilled at manipulating LiDAR data than anyone else.” Which is why, when Moore found some suspiciously tall trees in Sequoia National Park through a rudimentary LiDAR work-up in the course of his PhD research, he gave Taylor the LiDAR data for closer analysis. In 2018, Taylor processed the data and found five trees that looked huge indeed.

“95 m (311.7 ft) is the upper echelon for giant sequoia; it’s a threshold that’s hard to beat,” explained Taylor, whose LiDAR work nevertheless pointed to a few 95 m trees in an unusual landscape position.

The tallest known living giant sequoia measured 96.5 m when Sillett climbed it in 2016. Aside from this tree, nothing over 95 m had been found in decades of climbing and carefully searching through the tallest giant sequoias.

Yet the LiDAR seemed to show a mega tall grove of giant sequoia pushing 95 m that had somehow been completely overlooked. It also showed a few very tall trees nearby.

For a while, Taylor and Moore did not tell the ever-excitable Sillett about the monster sequoias lurking in obscurity because they enjoyed the idea of surprising him with the news once they had taken good laser measurements of the trees, but conditions and schedules did not allow them to make the trek down to Sequoia National Park right away. When they finally did tell Sillett about the prospective monarchs, he was absolutely amazed.

“We’d been all through those woods for the past 20 years and thought we’d measured everything. I couldn’t believe we missed something like this,” Sillett said, who then added, “But of course that is the advantage of LiDAR, because it sees the spots that you otherwise would miss. That this grove was completely unknown to any of us was the most exciting part!”

When COVID-19 struck, it kept the men from traveling to measure the trees. By spring of 2021, the trio was itching to find out if the trees could possibly be as tall as the LiDAR foretold. Taylor and Sillett wanted to share the joy of exploring a brand-new grove of giant sequoias with their fellow big tree lovers so they arranged with Fisher, Montague, Moore, and the others to meet up in Sequoia National Park.

When the whole crew of tree experts convened in Sequoia National Park, they were elated to be together on an exciting new mission yet appalled by the state of the forest.

“The area was clearly in distress,” Taylor said.

Many of the giant sequoia sported brown needles and looked very poor. According to Sillett, this is rare. Even worse, he said, was the fact that, “There were actually standing giant sequoias of considerable size, including some very big ones, that were completely dead.” The park service had been studying this unusual and alarming situation and had discovered that a beetle that normally affects incense cedar was attacking the giant sequoia.

Drought and disease had even more severely ravaged formerly stately and impressive sugar, Jeffrey, and ponderosa pines interspersed among the giant sequoia. Extremely hot, dry conditions had stressed even the tallest and previously strongest pines, and bark beetles had swept through and quickly finished off the weakened trees.

“All of the best pines were dead. Every one of them. We were really bummed when we were walking through there. It was very sad, very depressing,” Sillett recounted.

The entire crew was shaken by the ominous sensation of being in a dead and dying forest that felt like a giant tinderbox.

“It’s all we talked about,” said Taylor. “How, if a fire comes through here, all these trees are toast.”

Antoine added, “The place felt spooky. After many years of studying the trees in this general area, it was heartbreaking to know we were probably seeing the intact forest for the last time.”

Early on the first day of the trip, the team came across a shocking scene: a rattlesnake with a gray squirrel halfway down its throat. They left the animals alone but later returned to find that the snake had disgorged the dead squirrel when its jaws could not accommodate the rodent’s hips. Montague felt the scene carried a portentous message: “Don’t bite off more than you can chew.”

As Fisher put it, roughly a century of fire suppression has created an "abominable" mess in our forests and made them more

difficult to manage, particularly in the face of rising global temperatures and hotter drought. Indeed, removing fire from the giant sequoia ecosystem – which historically experienced low intensity burns every ten years or so that allowed seeds to germinate and grow in the newly enriched soil and open spaces created by fire – has led to severely overstocked ladder fuels, excessive white fir and incense cedar, and dangerously low sequoia regeneration. This situation – which is notunique to giant sequoia – is exacerbated by climate change, which allows pests and severe fires to proliferate while otherwise producing hotter, drier, windier and overall harsher weather and growing conditions.

Giant sequoia garner attention and concern because it is such a rare and charismatic species, but improving forest health by reducing overloaded forest fuels, reintroducing fire, and rebalancing species composition is extremely important across California and elsewhere.

To this end, Fisher and all of the others are strong proponents of policies and practices like hand-thinning, mechanical removal, and prescribed burns to stimulate and sustain overall forest health.

As passionate tree lovers, they all care deeply about understanding and fostering the conditions that will support elite trees well into the future. Finding and studying superlative specimens conveniently co-generates important data and attention around the needs of our forests. Plus, the heady rush of being the first to document magnificent trees of enormous proportions is exhilaratingly fun.

Although the brittle, dust-dry forest studded with declining pines and sequoias created a palpable sense of impending doom, the crew was anxious to explore the new stand of sequoias.

Interestingly, the tantalizingly unexplored area of supposedly tall trees didn’t look like anything special even as the team approached from below, for it was perched on a steep hillside.

“From where you drive by or where you walk the nearby trail, it doesn’t appear like anything that’s worth going to. You would never even think of it,” said Sillett.

It was an arduous trek up into the grove, yet as soon as the group entered they could tell that it was very special indeed. A surface spring trickled down from the upper edge of the mountainside and fed the entire stand. The magic of stepping into a previously unknown grove hidden away like a secret, naturally watered garden transported them all. The pure joy of laying eyes – perhaps for the first time ever – on the cluster of truly spectacularly tall trees elicited whoops and hollers.

“We were all excited, but Michael most of all,” Fisher noted.

Taylor is supercharged by tall trees, and he immediately began bounding around on his virtually spring-loaded feet taking laser measurements with Sillett. As the explorers computed the heights of the trees around them, they were astonished to confirm multiple trees over 95 m, others over 93 m, and more over 90 m.

They quickly realized that they had just found the tallest little grove of giant sequoias in the world.

Taylor and Sillett taking laser measurements of the "tallest little grove." Notice the greenery and surface water between the two men. Photo courtesy of Ken Fisher.

The trees were mostly very tall, some quite thick, and overall very healthy looking thanks to the relative abundance of water compared to everything else in the suffering area. The tallest tree in the grove was a record-setting 95.7 m. A 95.4 m tree of great mass and with a very lush crown was arguably the most beautiful specimen; it now ranks as the third tallest giant sequoia. Incredibly, the tallest tree in the grove did not take the title of “second tallest giant sequoia in the world” outright, because the team actually found another tree of exactly the same height in another location the next day. Regardless, the health, height, and beauty of the “tallest little grove” surpassed everyone’s expectations.

“It was simply a delightful pocket of forest, a small grove of true monarchs,” Montague said dreamily.

Unfortunately, Montague’s use of the past tense is apt. Just as the exploratory party had feared and felt in their bones, mere months after the “tallest little grove” was discovered, the disastrous KNP Complex Fire swept through the area.

According to the heat maps, the fire lingered for almost a week in the area where the tall sequoias had so recently been found.

Nobody has been back yet to check on the fate of those magisterial giants – but thanks to a new contract with the Pacific Forest Trust funded by Fisher, Taylor’s work for the next few years will be focused on California and revisiting the “tallest little grove” is a top priority for this summer.

What will he find when he returns? Will the results be tragic or, perhaps, glorious? Though the sugar pines are all assuredly dead, the grand, old giant sequoias with their very thick bark and miraculous water supply may have survived the blaze. For now, we can only hope for the best and wait for Taylor’s update.

1458 Mt. Rainier Drive, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96150 | (650) 814-nine565 | admin@sugarpinefoundation.org