HUNTING GIANTS

Tahoe Quarterly Feature on Michael Taylor and the Sugar Pine Foundation by Matt Jones

California is home to some of the biggest trees in the world. Redwoods, Douglas firs and Sitka spruces that tower over the lush forests of the north coast. Giant sequoias of incomprehensible girth scattered across disparate groves of the Sierra Nevada. Stately sugar pines stretching skyward from the shores of Lake Tahoe, their massive cones dangling from disheveled branches.

By any measure, the Golden State is a veritable wonderland of arboreal giants.

MATURE SUGAR PINES—THE TALLEST OF ALL PINE SPECIES—TOWER OVER CRYSTAL BAY ON TAHOE’S NORTH SHORE, PHOTO BY SYLAS WRIGHT

For this reason, it should come as no surprise that California is also home to some of the world’s leading forest researchers. Renowned big-tree hunters the likes of Michael Taylor and Stephen Sillett, whose pioneering feats of redwood discovery are documented in the 2007 book The Wild Trees. Tree-climbing aficionados such as Anthony Ambrose and Wendy Baxter, whose South Lake Tahoe nonprofit, The Marmot Society, is devoted to studying and protecting the state’s ancient forests. And the Sugar Pine Foundation, a South Lake Tahoe nonprofit committed to fighting the devastating effects of white pine blister rust.

These experts seek to not only find, measure, study and preserve the tallest and most iconic trees on the planet, but also to illuminate the outsized role the organisms play in monitoring the health of entire ecosystems. They live for the thrill of the find and the sheer love of large old-growth trees, which are increasingly under threat and in need of assistance across a warming, wildfire-ravaged landscape. With any luck, their passion and efforts will help keep these natural wonders alive long after we are gone, inspiring future generations with their longevity and grandeur.

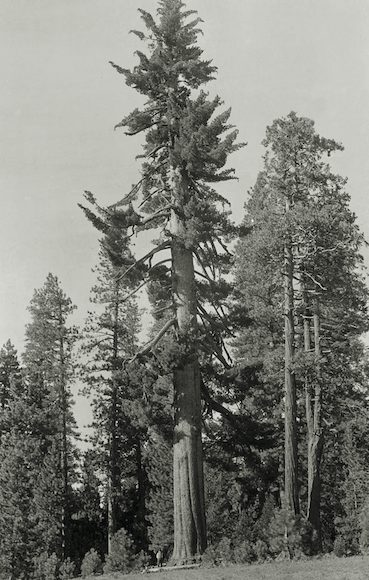

A STATELY TAHOE SUGAR PINE AT SUNRISE, PHOTO BY TOM LOTSHAW, COURTESY TRPA

WHERE BIG TREES REIGN

Pinus lambertiana, better known as sugar pine, has a range that runs through the inland mountains from Baja California all the way to Oregon. While they are not as big as the coast redwood or giant sequoia, they are the tallest known species of pine. The trees often grow up to 200 feet tall, though the most impressive specimens, many of which can be found in the Sierra Nevada, are far taller.

DUNCAN KENNEDY LEANS AGAINST THE REDONKULOUS TREE, THE SECOND TALLEST KNOWN SUGAR PINE, DISCOVERED ON THE WESTERN SLOPE OF THE TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST IN 2020, PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL TAYLOR

Michael Taylor has tracked down record-breaking sugar pines for nearly two decades and, since 2014, has reported his findings to the Sugar Pine Foundation.

Taylor discovered the tallest known sugar pine, a 273.74-footer dubbed Tioga Tower, in Yosemite National Park in 2015. In October 2020, he located the second, third and sixth tallest sugar pines in the world with friend Duncan Kennedy. Those trees, all found in the Tahoe National Forest on the western slope of the Sierra, measured 267.5, 267.15 and 263.7 feet, respectively. The biggest of the bunch, which Taylor named the Redonkulous tree, is 10.3 feet in diameter at breast height and an estimated 500 years old. Coincidentally, Taylor also discovered the tallest known white fir, standing over 261 feet, in the same general area west of Lake Tahoe.

“I always loved trees as a kid,” Taylor says. “I love big, giant trees. The bigger and taller, the better.”

This love is not only reflected in his work in the Lake Tahoe region. Taylor grew up in Santa Barbara, where he was first enamored with the redwoods of the local botanic garden. He now resides in a small town near the eastern edge of Shasta Trinity National Forest, which contains the largest known ponderosa pine in the country, at 235 feet tall and 8.3 feet in diameter.

In his three decades as a big-tree hunter, Taylor has discovered dozens of the world’s largest trees. These include the tallest known tree on earth, a coast redwood named Hyperion in Humboldt County, which measured 379.1 feet when Taylor co-discovered it with Chris Atkins in 2006 (the tree has since grown to 381 feet). In 2021, Taylor and Tressa Gibbard of the Sugar Pine Foundation co-discovered the tallest known Sitka spruce, standing 328.5 feet over the coastal forest of Northern California. And, this year, Taylor and Sillett located the second tallest Douglas fir, at 326 feet, also near the Northern California coast. (For perspective, the Statue of Liberty is 305 feet tall.)

In this way, what Taylor really means when he says that he loves big trees is that he loves finding big trees. It is not enough to know that they exist amongst thousands of acres of other giants. He wants their exact coordinates and measurements.

There is, however, a conundrum at the heart of hunting down the world’s tallest living organisms. Once a tree has been found, climbed and measured, the only piece of information to remain confidential is, in fact, the specimen’s precise location.

“Unless someone has a need to know, we tend to keep them a secret,” Taylor says.

TALL TREES OF OLD

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was believed that the world’s tallest trees could be found in Australia, where eucalyptus in the Dandenong Ranges were rumored to reach heights over 400 feet.

In the summer of 1938, members of the California Redwood Empire Association decided to lay such rumors to rest. They wrote a sternly worded letter to F.A. Silcox, chief of the U.S. Forest Service, imploring him to more closely inspect Northern California’s coastal forests. There, they believed, he would surely find a tree that stretched higher than any Australian eucalyptus.

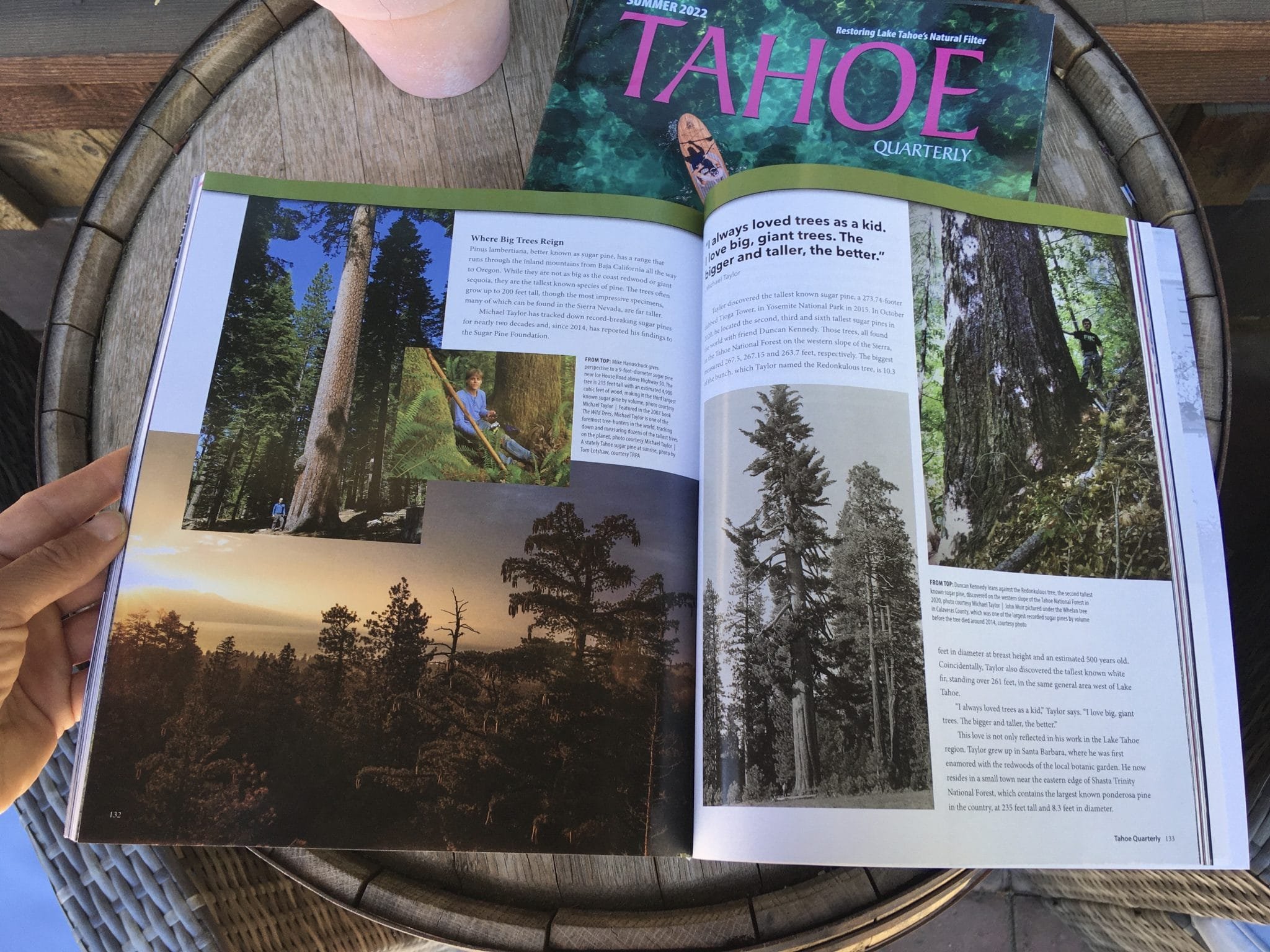

JOHN MUIR PICTURED UNDER THE WHELAN TREE IN CALAVERAS COUNTY, WHICH WAS ONE OF THE LARGEST RECORDED SUGAR PINES BY VOLUME BEFORE THE TREE DIED AROUND 2014, COURTESY PHOTO

In fact, they already had a particular tree in mind: a 364-foot behemoth that had been discovered by surveyors in 1931. The coast redwood had been named the Founders Tree to honor the three men who founded the Save the Redwoods League.

The forest service responded with a 115-page public report entitled Famous Trees. “As evidenced in the booklet … the tallest tree now known is a California Redwood,” wrote S.B. Show, a regional forester.

The pamphlet concluded that the Founders Tree was 39 feet taller than Australia’s largest eucalyptus, which, at the time, measured 325 feet.

That’s not to say there weren’t taller trees before then—colossal old-growth specimens that fell victim to the saw long before forest conservation was a thing.

In fact, according to Australian Geographic magazine, a mountain ash in southeastern Australia that was cut in 1880 measured over 375 feet. Meanwhile in America’s Pacific Northwest—before the virgin coastal forests were extensively logged starting in the nineteenth century—Douglas firs often grew to over 300 feet, with some forests containing 1,000-year-old relics that surpassed 400 feet. According to a report by the Sugar Pine Foundation, Douglas fir may have been the tallest tree species in the world before being logged, with the tallest reliably measured tree standing 393 feet (some 12 feet taller than Hyperion) and measuring 15.4 feet in diameter.

But Douglas firs of that size and age are long gone—just as the largest ancient redwoods may well have been lost to logging.

“This species (Douglas fir) was persecuted even worse than the redwoods,” Sillett, a professor of Botany at Cal Poly Humboldt, told the Sugar Pine Foundation, adding that the remaining Douglas firs are mere “table scraps” of the old-growth forests that once existed.

Nevertheless, the Forest Service’s Famous Trees report inspired other Americans to track down the biggest trees the country had to offer.

In September of 1940, American Forests Magazine published Let’s Find and Save the Biggest Trees, a letter by Joseph L. Stearns. The two-page missive issued a challenge to readers to locate the “largest specimens of our major species,” and to take “concerted action to bring about the protection and preservation of these great old giants.”

The magazine’s editorial staff heartily endorsed the letter, writing, “If you know of a very large tree, make it your business to see that its full accurate record is sent to the American Forestry Association.”

This record was to include the species, circumference, precise location and, of course, the height. Though, if history had demonstrated anything, it was that accurately measuring a giant tree was easier said than done.

MEASURING MONSTERS OF NATURE

There is more than one way to measure a tree.

In the 1940s, planes took aerial photographs of forests and then measured the shadow extending from a given tree to determine its height. Unfortunately, this method was both limited and imprecise. Sloping ground has the tendency to drastically shorten or lengthen shadows. In dense stands, shadows are often not visible enough to measure.

ANTHONY AMBROSE PREPARES TO ESTABLISH A CLIMBING LINE IN A STUDY TREE USING A CROSSBOW AND FISHING LINE, PHOTO BY WENDY BAXTER

Triangulation is still a relatively popular approach to estimating height. It requires standing far enough away from a tree to have a clear view of its top. Then, with the help of some mathematical wizardry, an imaginary right triangle is used to determine the distance between the tree’s base and crown.

The tallest sugar pine in Oregon, a 265-footer located in Douglas County, was estimated via triangulation in 2011. Needless to say, this method depends on the experience of the person doing the measuring. When two professionals scaled the same tree a year later, the height was proven to be closer to 255 feet.

“The most accurate way to measure a tree is to climb to the top and drop some [measuring] tape down,” says Anthony Ambrose of The Marmot Society.

Ambrose and his partner, Wendy Baxter, used to work as researchers at UC Berkeley, but in 2019 they left the Bay Area to get closer to nature and resettled in South Lake Tahoe. Shortly after, they launched The Marmot Society with a mission to conduct scientific research to understand how ancient forests function and how environmental change is impacting them. They are also co-founders of Canopy Dynamics LLC, which, among other things, specializes in facilitating projects that require access to a forest’s canopy. Together, they have climbed, rigged, studied and measured hundreds of trees, from sequoias and redwoods to Douglas firs and Jeffrey pines.

The approach of climbing to the top of a tree and dropping measuring tape down sounds like a relatively obvious solution to accurately discerning a precise height. Getting to the top of a 300-plus-foot tree, however, is deeply labor-intensive, to say the least.

For larger species like redwoods, Ambrose and Baxter first have to rig the tree for climbing. To do this, they use a fishing reel fitted to a crossbow and fishing line attached to blunted fiberglass arrows. After firing the arrow up into the tree, the fishing line hopefully goes over a large branch or two before descending back to earth. For shorter trees like oaks, the duo uses an item known as a Big Shot, which is essentially an enormous slingshot that can be purchased from various arborist magazines.

“Working as a team of two, we can usually, typically, on average, get two trees rigged in a day,” Ambrose says. “If the line is already set up and we’re just climbing the rope, it can take 15 to 30 minutes to get to the top of a really tall tree.”

ANTHONY AMBROSE MEASURES THE TRUNK DIAMETER OF A STUDY TREE IN MERCED GROVE, YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, PHOTO BY WENDY BAXTER

Climbing these leviathans has its rewards. Not many people have experienced life from the top of a redwood canopy, and once they’re there, they don’t always want to come back down.

“A lot of the time we spend in the tree is for our work, but sometimes we’ll stay up to watch the sunset from the top,” Ambrose says. If they climb a tree in the dark, they might hang out to see the sunrise.

While they recognize that they’re in a particularly dangerous line of work, Ambrose and Baxter have a perfect safety record in the 25 years they’ve been climbing.

There is yet another reliable way of measuring tree heights, one that doesn’t require a person to leave the ground.

“You can use lasers from the ground as well,” Ambrose says. “Some people, like Michael Taylor, are really, really good at measuring tree height from the ground using lasers. He’s phenomenally good at that, better than most people on the planet.”

In fact, Taylor has developed a method of discovering and measuring trees that doesn’t even require him to leave his house, at least not at first.

LASER PRECISION

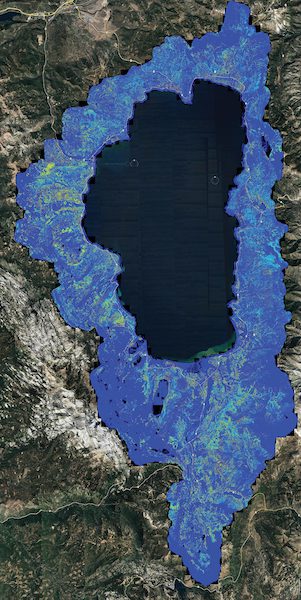

LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, uses laser technology to create 3D maps of terrestrial features. Government agencies like NASA, NOAA and the U.S. Geological Survey all collect LiDAR data, which is made publicly available.

FEATURED IN THE 2007 BOOK THE WILD TREES, MICHAEL TAYLOR IS ONE OF THE FOREMOST TREE-HUNTERS IN THE WORLD, TRACKING DOWN AND MEASURING DOZENS OF THE TALLEST TREES ON THE PLANET, PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL TAYLOR

“Each agency of the forest service generally processes their LiDAR and they know about most of those trees within their jurisdictions,” Taylor says. “But they’re not forthcoming about the coordinates. They don’t just give that information away. Basically, you have to process that LiDAR yourself.”

Over the years, Taylor has developed his own method of manually interpreting terabytes upon terabytes of raw LiDAR data. Specifically, he uses the data to create Canopy Height Models, which visually display everything from tree height to trunk thickness and coloration, depending on the quality of the LiDAR.

He recently completed a two-year project processing all the available LiDAR data that Oregon and Washington have to offer. Now, he has his sights set on the forests of California, including the Lake Tahoe Basin.

“Something that would take many, many lifetimes, I can do in a matter of months to years. Just one person, doing armchair exploring,” he says.

In this way, Taylor can trade bushwhacking through forests for navigating through terabytes of virtual data—which, while performed in the comfort of his home, is no simple task.

“We’re talking about massive, massive data here. I might have to get a one-quadrillion-byte hard drive,” he jokes.

It’s a time-consuming method, but processing and interpreting LiDAR is undeniably easier than trekking through dense forests and climbing up 300-foot behemoths. It also provides a more accurate height estimation than triangulation.

“You generally know the height within a half of a meter,” Taylor says.

Even so, he doesn’t simply locate a tree in the virtual point cloud and call it a day. After interpreting LiDAR to pinpoint the precise location and height of a tree, he then makes the physical trek to the actual site of the tree for confirmation—a painstaking process he calls “ground-truthing.”

A LIDAR MAP OF THE LAKE TAHOE BASIN INDICATES WHERE THE TALLEST TREES ARE LOCATED, PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL TAYLOR

“Much more work and risk are involved in going to and measuring the tree. A lot of the journeys we go on are extremely rigorous,” Taylor says. “Some of these places we’re going are absolute hellholes.”

In some ways, Taylor is being literal here. For instance, on a recent trip to Oregon to locate the world’s tallest known Douglas fir, at 326.4 feet, he had to descend into a deep ravine covered in devil’s club, a thorny understory shrub native to the Pacific Northwest.

“They have these spines, and when they hit you, they embed in you and they fester and get infected. They go right through your clothes. They penetrate everything,” Taylor says.

So while LiDAR has not completely eliminated the need to venture into rugged terrain, it has at least given researchers like Taylor a more accurate picture of what they can expect to find when they do make that inevitable expedition into the wooded unknown.

Plus, commercial LiDAR can reveal other important scientific information.

“With very high-resolution LiDAR,” Taylor says, “you can literally determine the species of every little tree under the canopy. You can figure out the amount of carbon in a forest and, more importantly, the amount of total carbon sequestration by knowing the characteristics of each species.”

This particular application of LiDAR, measuring the role that trees play in capturing and storing carbon, sheds light on the importance of protecting the world’s largest specimens.

Forests store and sequester carbon in their trees and soil, with large old-growth trees storing disproportionately massive amounts of carbon. This captured carbon is crucial in mitigating climate change.

These giants also contribute significantly to a forest’s biodiversity and, in effect, the ecosystem’s overall stability. For this reason, Taylor refers to the tallest trees as “boundary conditions.” The record-holders of any given forest are reflective of the environmental conditions that enabled them to break records in the first place.

“Typically, when something changes in the environment, the very tallest trees will be affected first,” Taylor says.

So, if the tallest trees are suffering, then the greater forest is also likely at risk. The inverse of this is also true: Protecting the overall health of a forest is one of the best ways of ensuring the survival of its tallest trees.

CITIZEN BIG-TREE HUNTING

It’s worth noting that you don’t have to be a certified forester or canopy researcher to track down and measure big trees. In fact, amateur naturalists and outdoor enthusiasts can nominate their own finds through a variety of organizations.

The American Forests Champion Tree Registry, which produces an annual list of new tree discoveries, also provides a comprehensive “Measuring Guideline Handbook” that explains various approaches to estimating a tree’s height, and that even includes a couple of recommendations for smartphone apps that make the process is a bit more accessible.

The Lake Tahoe Basin also maintains its own Big Tree Register that follows the same procedures that the American Forestry Association uses for documenting big trees. While the Tahoe Basin may not contain any world records, there are still impressive specimens worth tracking down. Case in point: Taylor’s LiDAR data reveals a roughly 214-foot white fir overlooking Emerald Bay.

But a tree doesn’t even have to be a giant to be worth nominating, as explained in the official Lake Tahoe Basin Big Tree Register booklet, “just large for its species.”

For those who are less interested in hunting down new giants and who are more intrigued by the idea of appreciating large trees that have already been discovered, The Marmot Society has a plan.

“Just recently, we did apply for a Tahoe Fund opportunity to try to start doing some recreational climbing,” says Wendy Baxter.

While they weren’t chosen for a grant this time around, Baxter says they hope to occasionally offer free recreational climbs of trees in the Tahoe Basin in addition to paid climbing experiences.

“Most people we’ve taken climbing say it’s one of the coolest experiences of their lives,” Ambrose says. “Going up even 100 feet in a pine tree gives you a unique perspective and a deeper appreciation of the trees themselves and the forest around you.”

Of course, if you’re averse to heights and not a huge fan of hiking off the beaten path in search of the next Basin champion, there is yet another opportunity for getting up close and personal with potential giants.

FOSTERING FUTURE GIANTS

Every fall and spring, the Sugar Pine Foundation calls on volunteers to plant sugar pine seedlings throughout the

Tahoe Basin.

Sugar pines, which once historically accounted for approximately 25 percent of Tahoe’s forests, now comprise less than 5 percent of our forests’ species, largely due to logging, drought and a particularly deadly non-native fungus called white pine blister rust. In fact, an estimated 90 percent of infected sugar pines will not survive.

THE SUGAR PINE FOUNDATION FACILITATES THE PLANTING OF ABOUT 10,000 FUNGUS-RESISTANT SEEDLINGS PER YEAR, PHOTO COURTESY SUGAR PINE FOUNDATION

Since 2005, the Sugar Pine Foundation has sought out and tested individual trees to determine which, if any, are resistant to the disease. As of 2022, they have identified 66 fungus-resistant specimens throughout the Tahoe region. The pine cones produced by these trees are collected each fall and then germinated in a nursery. Once the seedlings are a year old, and still scarcely a foot tall, volunteers assemble to plant them across various restoration areas. The foundation typically facilitates the planting of about 10,000 trees per year.

It is difficult to say, at least with any accuracy, whether any particular seedling will become a record-breaking tree hundreds of years from now. More importantly, the reforestation project reveals that individual trees are still important to understanding and protecting the overall health of a forest. In this case, seeds are not selected for their genetic ability to become the tallest of their kind, but for their ability to grow into trees that can simply survive in an ever-changing and increasingly challenging climate.

“In our work, we are always looking ahead to the future to retain healthy, biodiverse forests that will be resilient even in the face of climate change, fire, pathogens and other threats,” says Maria Mircheva, executive director of the Sugar Pine Foundation. “It is important to us to help plant the seeds of stewardship in people’s minds while also planting seedlings that may be giant forest monarchs some day.”

Sugar pines planted in the Tahoe Basin today will not produce their own seeds until they are about 50 years old, meaning the volunteers who so carefully put those foot-tall seedlings into the earth may not live to see the fruits of their labor.

Even so, a certain trust in the imaginary has always been central to conservation efforts. Knowing what the future could look like if we lose our forests is inextricably linked to believing in what the future could look like if we save them. It just so happens that individual trees, whether famous champions or fledgling seedlings, are the sites at which these two seemingly oppositional forces first take root.

Matt Jones lives in Sparks. He can’t see many big trees from his apartment window, but he knows they’re out there, just beyond the horizon.

1458 Mt. Rainier Drive, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96150 | (650) 814-nine565 | admin@sugarpinefoundation.org